Australian men and women are both becoming more progressive across generations, my recent research shows. But young women are more left-leaning than young men—so there is a gender gap, reflecting a global trend.

It made me think: how is this gap reflected in romantic relationships?

To find out, I went back to the nationally representative Australian Election Study data, spanning 1996 to 2022—a period of roughly 25 years. This time, I was interested in whether a person’s political alignment matched their partner’s. I looked at the trends over time and across generational lines and found couples are increasingly likely to be in “politically mismatched” relationships.

Does higher education breed tolerance?

If half of romantically partnered Australians are now in politically mismatched couples, does this mean we’re becoming more tolerant of each other’s divergent views—at least when it comes to romance? And if so, why?

Increased levels of higher education, which have risen roughly 24% since 1996, might offer one explanation. While it’s often argued universities are breeding grounds for left-wing radicalism, as people become more educated, they become more open to different views.

I found people with a university education are roughly 30% more likely than those without one to have a politically mismatched partner.

But what else is happening?

How I reached my findings

After each federal election, the Australian Election Study survey asks respondents to place themselves (as well as their partners) on an 11-point ideological scale, where 0 is extreme left, 10 is extreme right, and 5 is often interpreted as neither left nor right (the political center).

Based on how voters place the parties in the ideological scale, I categorized ALP, Greens and Democrats as left matches, and Liberal, National and One Nation as right matches. Others who align with independents or no party are grouped in an “Other” category.

The Australian Election Survey does not survey couples, so I relied on each respondent’s reported perception of their partner’s political inclinations.

I analyzed this data, using six generational categories:

- War generation (born 1920s—1,356 participants)

- Builders (born between 1930 and end of WWII—3,665 participants)

- postwar Baby Boomers (born 1946–1960—5,611 participants)

- Gen X (born 1961–1979—4,578 participants)

- Millennials or Gen Y (born 1980–1994—1,447 participants)

- Gen Z (born after 1994—a smaller size of 280 participants).

Under 30s likely to be politically unmatched

Taken together, younger people make up the largest share of politically unmatched relationships: roughly 66% of those aged 18 to 30.

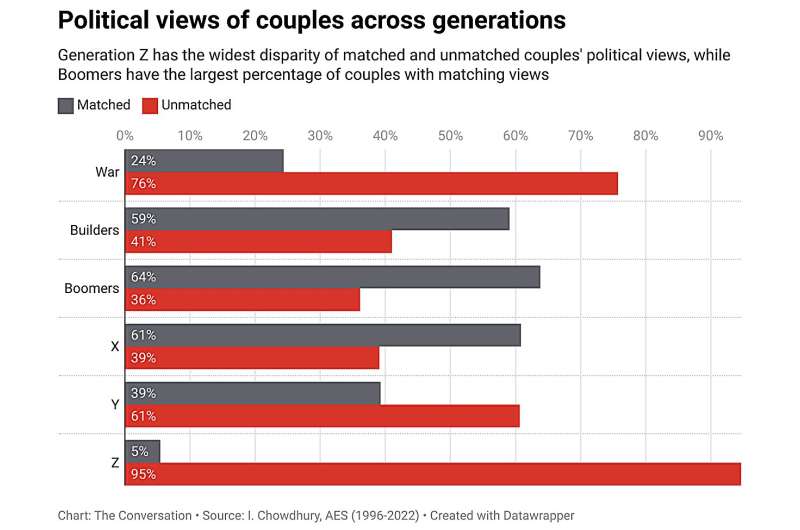

In the Australian Election Study, a whopping roughly 95% of Gen Z respondents reported politically unmatched relationships (though they represented a relatively smaller sample of the survey). And a still-high approximately 61% of millennials reported unmatched relationships.

This dropped significantly among Gen X (roughly 39%), Boomers (roughly 36%) and Builders (roughly 41%).

It rocketed again for the War generation, who had the second-largest share, after Gen Z: 76% reported politically unmatched relationships. I have a keen sense this reflects women being less active in politics than men when this age group was young and partnering up, more than 50 years ago.

Why might young people be more tolerant?

Millennials and Gen Z have grown up in a more diverse (multicultural) Australia than previous generations—and they’re exposed to more people from different political backgrounds. Contact between different groups can reduce prejudice and increase tolerance.

Younger generations have different values and are more likely to emphasize personal freedoms, social justice and environmental concerns. They identify more strongly with specific policy issues—and their party alignments may change accordingly from election to election.

This can make them more open to relationships with people with a similar stance on issues that mean something to them, rather than people who share a political party.

Attitudes towards dating, relationships and social norms have evolved, too. Millennials and Generation Z have grown up socializing and dating in the digital era, making them more likely to be exposed to people from diverse political contexts and views.

The global perspective of younger generations, who live in a world that fosters a more cosmopolitan outlook, may extend to relationships too.

Left-right changes and other influences

In 1996, the proportion of couples who both identify with the left was around 23%. Nearly 25 years later, it had dropped just two percentage points, to around 21%. Over the same time period, the proportion of couples who both identify with the right had dropped around 7%, or nearly three times as much: from around 29% to around 22%.

This suggests the 9% rise in politically mismatched couples over those nearly 25 years comes more from changes to the right than to the left, reflecting Australia’s broader move away from the right in that time.

Various lifestyle and socioeconomic factors are also relevant.

The higher the income, the more likely it is that couples will be politically matched: it’s 12% more likely with each move into a higher income bracket. And couples who own their houses (either outright or paying off a mortgage) are roughly four times more likely to be politically matched than those who are renting, living in social housing, or living with their parents.

And compared to “Very strong supporters” of a political party, “Fairly strong supporters” are roughly 11% less likely to report being politically matched to their partner, and “Not very strong supporters” are roughly 27% less likely. So, unsurprisingly, the more strongly someone is affiliated to a political party, the more likely they are to care about a partner having a different party alignment.

Right-leaning individuals are more likely to be politically matched than left-leaning individuals.

The gender gap

Women are approximately 34% less likely than men to be in a politically matched partnership.

Overall, among right-leaning matches there are more men (52%) than women (48%). This trend reverses on the left, with more women (52%) politically matched with their partners than men (48%). This seems to reflect my earlier findings that more Australian men identify with the right and more Australian women identify with the left.

Looking at generations, however, millennials were unusual in having no gender gap, with roughly 15% of both men and women in politically matched partnerships on the right. There is virtually no gap between men (61%) and women (60%) in politically unmatched partnerships. This suggests that, despite ideologies and gender, millennials are more tolerant of partners’ diverse views than previous generations.

While Gen Z displayed a similar absence of a gender gap (94% of men and 95% of women are in unmatched partnerships), it’s too early to draw conclusions about what this means. Some of its members are still under 18 and some have yet to vote, so are not yet reflected in the Australian Election Study.

Taken together, there is certainly a trend among younger people suggesting we have become more accepting of partners with differing political views. The increase in voter volatility and decline in lifetime party loyalty challenge the notion of rigid ideological categorizations. Instead, both men and women can oscillate between being “left” or “right” according to the issues.

However, while young people are increasingly tolerant of differing political leanings, values connected to specific issues may still be considered deal breakers in relationships.

Note: Due to data constraints in political surveys, I focus on individuals already in partnerships, omitting those who are single or actively seeking partners. As such, these analyses fail to account for the complexities inherent in romantic relationships today. With the rise of non-heterosexual partnerships and increase in volatile relationship dynamics, aggregate data may not fully explain unmatched values as potential deal-breakers among singles (especially women opting for singlehood) and nontraditional partners.

Provided by The Conversation