While the world focuses on US abortion rights after the overturning of the Roe v Wade ruling, women in Northern Ireland are still finding it difficult to access services. Those who do visit abortion clinics face protesters emboldened by what they view as success across the Atlantic.

The placards held resolutely by men standing at the hospital’s entrance are uncompromising.

“Abortion is murder,” they state, in large red lettering. “Global Holocausts,” says another, held by a protester from a group called Against Abortion NI.

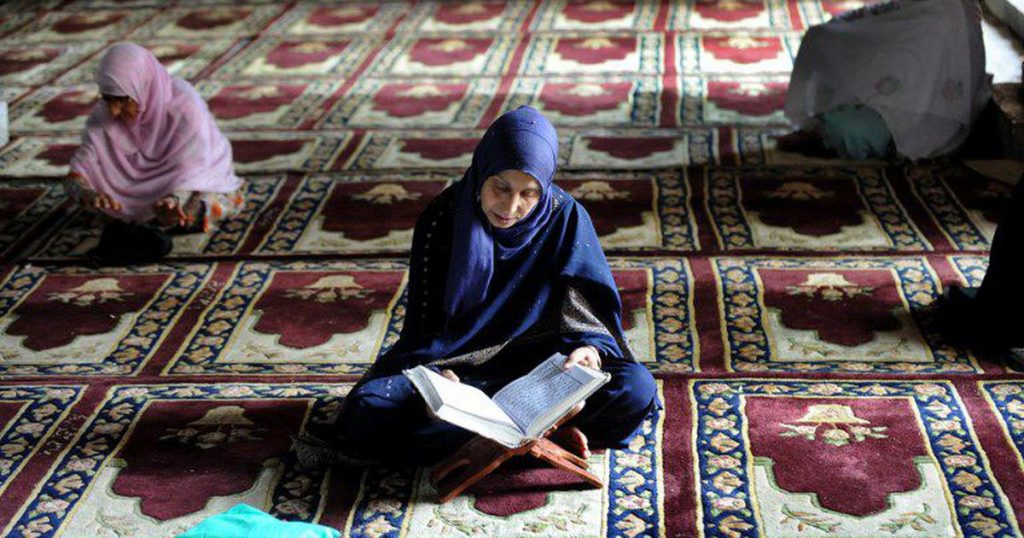

On the opposite side of the road outside Newry’s Daisy Hill Hospital a different group, also mostly male, are holding rosary beads and praying, displaying pictures of the Virgin Mary. They recite verses in unison, repetitively, without pause.

These anti-abortion demonstrations by groups from both the Catholic and Protestant communities have become a regular sight outside some of Northern Ireland’s hospitals.

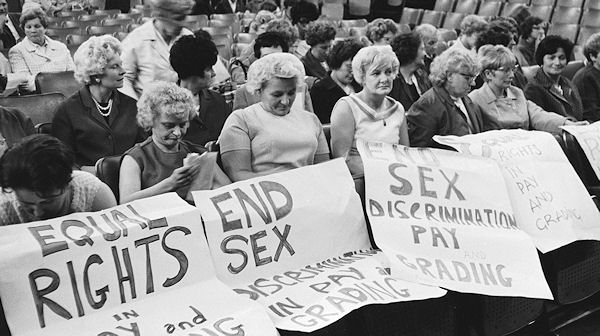

“What women have told us is it’s really intimidating coming up to these gates. It’s misogyny,” says Fiona, who volunteers as a chaperone to support women. She helped set up Supporting Women Newry in response to the regular protests which began after abortion was decriminalised in 2019.

The protesters feel they are doing an important job.

“We’re informing the public,” one man, who didn’t want to give his name, says. “Doctors aren’t gods, they don’t get the right to decide who lives and who dies.” They describe how one clinic closed down after their protest, which they consider a success.

More than 3,000 abortions have been carried out in Northern Ireland since the law changed. Despite this, last year 161 women flew to England to access abortions as there have not yet been sufficient services established to serve the demand. This is a significant decrease from 2018, the year before decriminalisation, when more than 1,000 women travelled for the procedure.

The delays to increasing provision have dragged on due to disagreements between the political parties. The DUP has blocked efforts to move services forward.

To try and resolve the stalemate, the UK government has given Northern Ireland Secretary Brandon Lewis new powers to compel the health service to set up wider services, which he plans to use within weeks.

The women who do manage to access the clinics often encounter anti-abortion protest groups.

Cara, another chaperone, says the group has been contacted by a wide variety of people who visit the hospital and object to the often very graphic protests.

“People are going in for counselling after having miscarriages and still births,” she says. “If you’re going in there to access any treatment, and this is a multi-use site, it’s intimidating and harassing.”

Efforts to address activity outside abortion services differ across the UK. Concerns over welfare led to the UK’s first so-called buffer zone being set up outside an abortion clinic in the London borough of Ealing in 2018. Pro-choice campaigners had hoped these would become the norm, but only two more have been created since then.

The Northern Ireland Assembly has voted to pass a law which would ban groups from demonstrating directly outside a heath facility. But it has been referred to the Supreme Court by the attorney general of Northern Ireland, to decide whether it conflicts with the right to protest.

The UK government says it is reviewing the issue in England and Wales. Meanwhile, earlier this week, Scotland’s first minister said legislation would be passed to enforce the zones.

The protests also take place at Craigavon Hospital, which Ashleigh Topley visited regularly during her first pregnancy. At one appointment she received the news her baby had a fatal foetal abnormality. She asked for an abortion but as it was prior to the law change, it was denied.

“Those appointments, some of them were very, very, difficult. Had I had to run the gauntlet of protesters, it would have made them even worse,” she said.

Having to continue her pregnancy to 35 weeks was extremely traumatic, she said, and it was very obvious she was pregnant.

“People would ask, ‘are you excited? What are you having?’ Sometimes I would tell the truth, that she was going to die. Other times I would just lie and pretend everything was OK,” she says.

Ashleigh says if she had been allowed an abortion, she could have had more control. “Waiting and waiting and waiting, that was just hardship, unnecessary hardship on top of one of the most awful periods of our lives.” Now, she feels deeply for the women who have to pass protesters.

“The grief and the experience they’re going through is so current and so recent, it’s just so cruel.”

Last week, the US Supreme Court struck down the landmark Roe v Wade decision, transforming abortion rights in America and allowing individual states to ban the procedure. This has re-energized abortion campaigns on both sides of the argument in Northern Ireland, with anti-abortion groups feeling encouraged by what is happening there.

“When a woman comes in they have a decision to make… some women in two years or 10 years’ time will be thanking us,” says a man outside the clinic.

He’s asked whether they are adding to the woman’s pain. “This is compassion,” he says. “Compassion for the baby”.

Northern Ireland’s health service is set to be compelled to provide more abortion services in future. What will now be decided by British Supreme Court judges is what kind of experience women will face when they come through the hospital gates.